Pay-to-publish journals: deceptive fee solicitations

Pay-to-publish academic journals often reach researchers with flattering invitations that look “official,” urgent, and selective. The pitch can feel routine in a busy academic inbox, especially when it includes a promised fast decision, special issue placement, or an “editorial board” role.

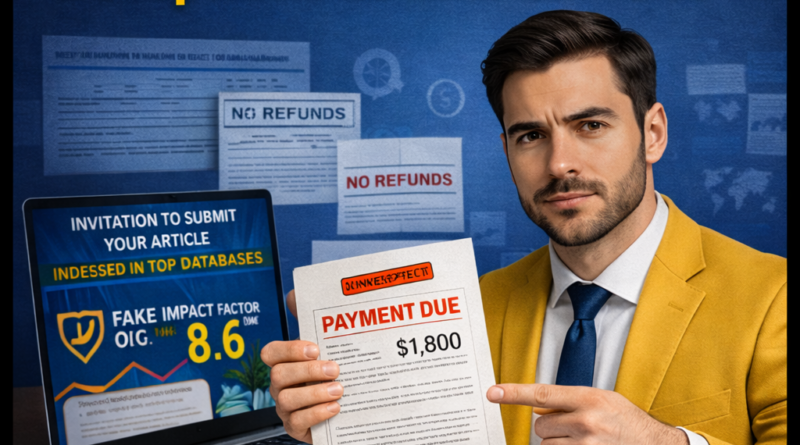

The problem is that some solicitations are deceptive: fees are obscured, indexing claims are exaggerated, peer review is minimal, and withdrawal policies are harsh. Understanding how to assess legitimacy helps avoid wasted funds, damaged credibility, and disputes over unexpected invoices.

- Hidden publication charges revealed late in the process

- Misleading indexing or impact factor representations

- Pressure tactics that shortcut real peer review

- Rigid withdrawal terms leading to billing disputes

Quick guide to pay-to-publish journal solicitations

- What it is: journal invitations tied to article processing charges, sometimes presented as prestigious opportunities.

- When issues arise: after submission acceptance, during “revision,” or at the invoice stage with short payment deadlines.

- Main legal area: consumer protection, contract terms, deceptive marketing, and unfair billing practices.

- Why it matters: unexpected fees, reputational harm, and disputes over withdrawal, copyright, and refunds.

- Basic path to address: document the solicitation, challenge misleading claims, request cancellation/refund, escalate to regulators or dispute channels if needed.

Understanding pay-to-publish solicitations in practice

Pay-to-publish models can be legitimate, especially in open access publishing, where an article processing charge supports editorial and hosting costs. The concern is not “fees” by themselves, but how fees and journal credentials are presented, and whether the promised editorial standards actually exist.

Deceptive solicitations often rely on confusion between reputable open access workflows and low-quality operations that prioritize volume over review. A quick legitimacy check usually focuses on transparency, verifiable indexing, editorial governance, and clear withdrawal terms.

- Fee transparency: charges stated clearly before submission, with a stable fee schedule.

- Verifiable journal identity: consistent publisher details, contact information, and ownership disclosures.

- Editorial process: realistic timelines, reviewer feedback, and documented standards.

- Indexing verification: claims match trusted databases, not vague “indexed internationally” wording.

- Contract clarity: author agreement explains copyright, licensing, and withdrawal rules.

- Late-stage invoices after “acceptance” are a frequent pressure point

- Indexing and impact metrics are commonly overstated or misrepresented

- Withdrawal penalties may appear only inside the author agreement

- Generic email templates often mimic real journals’ tone and structure

- Promises of fast publication can signal minimal peer review

Legal and practical aspects of pay-to-publish solicitations

Disputes typically center on misrepresentation (what was claimed about indexing, peer review, or prestige), disclosure (when fees and terms were presented), and contract formation (what the author actually agreed to and when). The practical outcome often depends on the written record: emails, submission screens, invoices, and the author agreement version.

When marketing claims are misleading or material terms were hidden, complaints may rely on unfair or deceptive practices rules, as well as contract doctrines about clarity and consent. However, platforms may argue that the author accepted terms through a clickwrap agreement or by submitting the manuscript.

- Disclosure checkpoints: fee schedule, withdrawal terms, and refund conditions displayed before submission.

- Representations relied on: indexing statements, “impact factor” wording, editorial board claims.

- Billing triggers: acceptance notice, proof stage, publication scheduling, DOI assignment.

- Common evidence: screenshots of submission pages, archived web pages, email headers, invoices, and policy PDFs.

Important differences and possible paths in pay-to-publish disputes

Not every paid journal is deceptive. The key differences are transparent open access publishing versus misleading or low-integrity solicitations that imply credentials they do not have. Another difference is whether the publisher provides a meaningful service (real review, editing, hosting) before charging.

- Legitimate OA journals: public fee schedule, real editorial board, verifiable indexing, documented review.

- Borderline operations: some transparency, but exaggerated metrics and unusually fast decisions.

- Deceptive solicitations: hidden fees, unverifiable indexing, pressure tactics, and unclear ownership.

- Special issue invitations: may be real or may be used to create urgency and social proof.

Possible paths typically include a documented cancellation/refund request, a negotiated resolution, or escalation through institutional channels. When payment was made by card, chargeback disputes may apply, but success depends on clear documentation and timing.

Escalation may involve a university research office, a professional society, consumer protection agencies, or payment processors. Each path has tradeoffs: direct negotiation can be faster, while formal channels may require more documentation but can increase leverage.

Practical application of pay-to-publish issues in real cases

Problems often appear after an enthusiastic invitation: the author submits, receives a rapid “acceptance,” and then encounters an invoice with a short deadline. In other cases, the author is told that withdrawal is not allowed after “processing,” even if peer review never occurred.

Graduate students, early-career researchers, and independent scholars are commonly affected because they may have less institutional guidance on journal vetting. The most useful evidence is usually the full solicitation chain and the version of the author agreement that governed the submission.

Further reading:

Relevant documents commonly include solicitation emails, the journal website fee page, submission portal screenshots, acceptance notices, invoices, DOI/publication status, and any withdrawal or refund policy language.

- Collect the record: save emails, download invoices, and screenshot fee pages and submission steps showing disclosures.

- Verify claims: confirm indexing and metrics via authoritative databases and the publisher’s identifiers.

- Send a structured request: ask for cancellation/refund, citing the specific misleading statements or missing disclosures.

- Track deadlines: note invoice due dates, withdrawal windows, and any “publication” milestones claimed by the publisher.

- Escalate if needed: use institutional support, payment disputes, and regulator complaints with the evidence packet.

Technical details and relevant updates

In many systems, the contract terms are embedded in clickwrap agreements and policy pages that can change over time. Capturing the exact policy version in effect on the submission date can be decisive, especially when the publisher later points to different language.

A common technical issue is the use of ambiguous metrics wording, such as “global impact factor” or “indexed in major databases,” without specifying which database and without a verifiable listing. Another frequent issue is the appearance of “editorial board” names that are hard to confirm through institutional profiles.

Where available, institutional library guidance and research integrity offices can help assess journal legitimacy and provide standardized checklists. Some universities maintain internal lists or advisories for high-pressure solicitations.

- Watch for policy drift: fee or withdrawal terms updated after submission.

- Confirm identifiers: ISSN, publisher address, and journal title consistency across pages.

- Validate indexing: rely on database listings rather than website banners.

- Preserve screenshots: submission steps and fee disclosures often disappear later.

Practical examples of pay-to-publish disputes

Example 1 (more detailed): A researcher receives a “special issue” invitation claiming indexing in a well-known database and a fast peer review. After submitting, the paper is accepted in 48 hours with minimal comments, followed by a $1,800 invoice due in 72 hours. The author tries to withdraw and is told a withdrawal fee applies because the manuscript is “in production.” The author compiles emails, captures screenshots showing the indexing claim, and requests cancellation based on misleading representations and late disclosure of material terms. The dispute proceeds through the institution’s research office and a payment processor, with the outcome depending on whether the publisher can document meaningful services provided before billing.

Example 2 (shorter): A graduate student submits to a journal that used a similar name to a reputable title. The fee schedule was not visible until after account creation. The student requests cancellation, attaching screenshots of the hidden fee flow and asking for written confirmation that the manuscript will not be published or licensed.

Common mistakes in pay-to-publish situations

- Relying on email claims without verifying indexing and metrics independently

- Submitting before confirming the full fee schedule and when charges are triggered

- Ignoring withdrawal and refund clauses buried in author agreements

- Failing to keep screenshots and copies of policy pages as they appeared

- Paying under time pressure without requesting written clarification

- Assuming a journal name implies affiliation with a reputable publisher

FAQ about pay-to-publish academic journal solicitations

Are publication fees automatically a sign of a deceptive journal?

No. Many reputable open access journals charge article processing fees and disclose them clearly. The concern arises when fees, indexing status, or peer review standards are misrepresented or disclosed only after submission milestones. The written record of disclosures and promises is usually central.

Who is most affected by deceptive solicitations?

Early-career researchers, graduate students, and independent scholars are often targeted because they may be seeking publication opportunities and may have less institutional vetting support. High-pressure timelines and “special issue” messaging can increase the chance of accidental acceptance of unfavorable terms.

What documents matter most when disputing an invoice or seeking a refund?

Key items include the full solicitation emails, screenshots of fee disclosures during submission, the author agreement in effect at the time, acceptance and invoice notices, and any pages claiming indexing or impact metrics. Clear dates and saved copies help address later disputes about what was shown and when.

Legal basis and case law

The main legal theories often involve unfair or deceptive acts and practices, misleading advertising, and contract enforceability based on disclosure and consent. Where a solicitation materially misstates indexing, peer review, or journal identity, the dispute may focus on whether those statements induced submission or payment.

Contract issues commonly turn on whether the author agreed to clear, accessible terms and whether key provisions were presented in a conspicuous way. Refund and withdrawal clauses may be challenged when they are inconsistent with prior representations or when the publisher cannot substantiate that promised services were actually performed.

Court outcomes and enforcement trends vary by jurisdiction, but disputes frequently emphasize the evidence trail and the clarity of online contracting steps. Authorities and courts generally examine the overall presentation: what a reasonable person would understand from the solicitation and the submission flow.

Final considerations

Deceptive pay-to-publish solicitations can create real financial and professional consequences, especially when fees and withdrawal terms surface late. A disciplined approach—verifying indexing, confirming fee triggers, and preserving the submission record—reduces the chance of unexpected invoices and hard-to-resolve disputes.

When a dispute happens, the most effective responses usually combine clear documentation with a structured cancellation or refund request tied to specific representations and disclosure failures. Escalation options exist, but outcomes often depend on timing and the completeness of evidence.

This content is for informational purposes only and does not replace individualized analysis of the specific case by an attorney or qualified professional.

Do you have any questions about this topic?

Join our legal community. Post your question and get guidance from other members.

⚖️ ACCESS GLOBAL FORUM